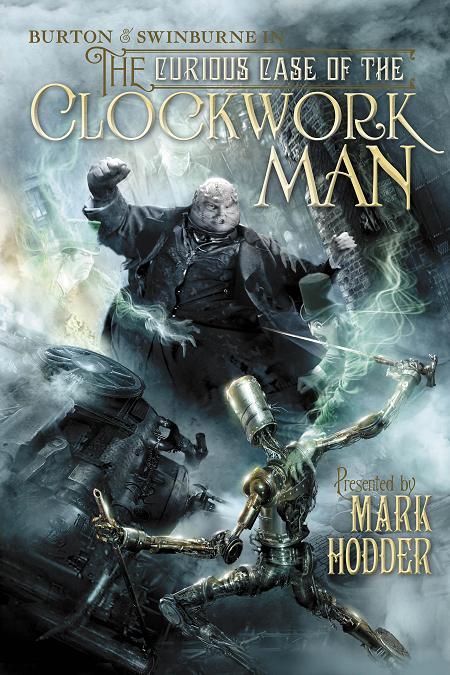

I put off reading my copy of Mark Hodder’s debut novel, The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack until the review copy of its sequel, The Curious Case of the Clockwork Man, arrived. We’re told not to judge a book by its cover, but the covers of many PYR releases, and those by Jon Sullivan in particular, challenge our ability to reserve judgment. The image of a brassy looking automaton drawing a sword-cane to square off against a massive, patchwork-looking figure (a seemingly steampunk Kingpin), surrounded by spectral figures (steam wraiths!) in flight was too much to resist. Accordingly I set to work devouring Spring Heeled Jack, a phenomenal first novel deserving of the recently won Philip K. Dick award. As I said at Steampunk Scholar, if this is what the “punk” Hodder wants to see steampunk look like, then I say with Oliver Twist, “Please, sir, I want some more.”

And more there is. The Curious Case of the Clockwork Man is a worthy successor to Spring Heeled Jack, combining a number of seemingly clichéd steampunk elements in ways that shatter and rebuild them: the combination of industrial and biological sciences ala Westerfeld’s Leviathan; the filthy London of Gibson and Sterling’s Difference Engine, filled with anachronistic innovations; recursive fantasy blending both historical and literary figures as in Newman’s Anno Dracula; the Agent of the Crown, seen in Green’s Pax Britannia series; the labyrinthine schemes of secret societies in Dahlquist’s The Glass Books of the Dream Eaters and Tidhar’s Camera Obscura; multi-threaded plots akin to Powers’ Anubis Gates; and the quirky humor of Blaylock’s Adventures of Langdon St. Ives. Where these predecessors and contemporaries are inferior, Hodder elevates his material, and where they are masters of narrative, he matches them.

The story defies summary, but the narrative centers upon Sir Richard Francis Burton and poet Algernon Swinburne’s investigation into a theft of black diamonds, ultimately embroiling them in the affairs of a dubious claimant, supposedly the heir of a cursed estate. As with Anubis Gates, this only scratches the surface of Hodder’s tale, as his secondary world-building is delightfully dense. Readers familiar with nineteenth century will enjoy the numerous changes Hodder has wrought, which take this simple plotline and render it complex. The Curious Case of the Clockwork Man clearly demontrates Hodder’s ability for making the vast elements of his secondary world cohere, live, and breathe, and to do it in a way that is deliciously entertaining.

Take the introduction of a new vehicle built by from the carapace of an insect, grown “to the size of a milk wagon” by the Eugenicists, the biological faction of steampunk technology:

“You’re missing the point entirely. It’s not a species of vehicle, it’s a species of insect; and not just any insect, but the one held sacred by the ancient Egyptians! They are being grown on farms and summarily executed, without so much as a by your leave, for the express purpose of supplying a ready-made shell! And the Technologists have the temerity to name this vehicle the Folks’ Wagon! It is not a wagon! It’s a beetle! It’s a living creature which mankind is mercilessly exploiting for its own ends. It’s sacrilege!” (p. 211)

It’s a wonderfully wild and whimsical moment of humor via steampunk technology, followed by Burton’s observation that the “exploitation of the working classes by the aristocracy” is more monstrous than the construction of this steampunk VW Beetle. The scene is exemplary of how Hodder blends gonzo gadgetry with humor, strong character voice, social commentary, and a comprehensive awareness of the historical implications of his ideas.

Like many steampunk writers, Hodder revels in the question, “wouldn’t it be cool if…?” Unlike many steampunk writers, he takes a step further, giving reasons why the impossible is possible in his secondary world. He then postulates both the potential benefits and downside of these innovations, such as ornithopters which fly at great speed, covering “enormous distances without refuelling,” but are “impossible for a person to control; human reactions simply weren’t fast enough to compensate for their innate instability” (39). There are intelligent messenger parakeets which can relay a message audibly, but insert their own foul-mouthed colloquialisms, such as “dung-squeezer” and “dirty shunt-knobbler” (58).

For every progression, there is a problem. As one character observes, “if the dashed scientists don’t slow down and plan ahead with something at least resembling foresight and responsibility, London is going to grind to a complete standstill, mark my words!” (72). There is romantic high adventure in Hodder’s steampunk world, but also an underside of gritty realism. It is this tension between the playful and the serious that makes Hodder’s work stand out. Imagine Gail Carriger’s humor and Cherie Priest’s kick-ass adventure wrapped up in one book, and you get Hodder’s Clockwork Man.

Hodder’s historical reflections via action set-pieces are his strength, not only for counterfactual play with technological cause and effect, but also for the use of possible worlds theory as it relates to alternate history. Hodder understands what sort of universe is necessary for steampunk scenarios: it isn’t one where simply a moment in history has changed. A volunteer at the recent Canadian National Steampunk Exhibition in Toronto welcomed us “from all your steampunk worlds.” Steampunk is rarely only history zigging when in actuality, it zagged. It isn’t just about alternate history; it’s about alternate worlds. As Countess Sabina, a fortune teller, admits to Burton, “Prognostication, cheiromancy, spiritualism—these things are spoken of in the other history, but they do not work there…” to which Burton adds, “there is one thing we can be certain of: changing time cannot possible alter natural laws” (57). The conversation admits an aspect of the steampunk aesthetic that is problematic for those who see steampunk as science fiction without a shred of fantasy.

While alternate history is often equated with steampunk, steampunk is rarely alternate history. A key difference exists: alternate history posits one moment of historical divergence, but does not abandon laws of the physical universe in the process. Steampunk occurs in an alternative world, not an alternate timeline, a space-time setting with different physical laws than our own, where cavorite, aether, or all pretense abandoned, magic makes things work. This difference may seem minimal, but I contend, as the Encyclopedia of Fantasy does, that it is “crucial”:

If a story presents the alteration of some specific event as a premise from which to argue a new version of history … then that story is likely to be sf. If, however, a story presents a different version of the history of Earth without arguing the difference—favorite differences include the significant, history-changing presence of magic, or of actively participating gods, or of Atlantis or other lost lands, or of crosshatches with otherworlds—then that story is likely to be fantasy. (John Clute “Alternate Worlds,” p. 21)

The inclusion of fantasy elements in a world resembling ours is an alternate world, not an alternate history. The inclusion of fantasy elements does not mean, as Clute states, that steampunk is only fantasy and not SF. Steampunk is neither SF nor fantasy, but an aesthetic both genres employ.

What’s wonderful about Hodder is that he’s aware of this. His characters are aware of this. And due to the awareness, Hodder argues the difference of Clute’s article. There are fantasy elements in Clockwork Man, but their inclusion has its foundation in the conundrum of time travel’s impact. Unlike many steampunk works that simply explain away their devices with technofantasy, Hodder includes discussions on the nature of history and ontology that are self-reflexive without becoming didactic. In other words, these ideas are embedded in the action and the dialogue: no Vernian info-dumps here.

Accordingly, Hodder’s Burton and Swinburne adventures have the potential to be accepted by a wide variety of steampunk fans, as well as readers who just enjoy a good science fiction or fantasy story. You can enjoy it as straight-up adventure, or revel in the social discourse or speculative digressions. While some reviews offhandedly tell you a novel has it all, I can say with confidence that, aside from romance, The Curious Case of the Clockwork Man really does have it all, at least for the steampunk aficionado: stuff will blow up, devious devices will be unveiled, intrigues will be exposed, and yes: unlike so many covers that lie to you, you will see the showdown between the clockwork man wielding that sword cane, and that massive patchwork monstrosity. All this, and a steampunk Volkswagon in the bargain.

Mike Perschon is a hypercreative scholar, musician, writer, and artist, a doctoral student at the University of Alberta, and on the English faculty at Grant MacEwan University.